Working capital is widely misunderstood

Posted by Toby York. Last updated: April 24, 2024

Working capital is a widely used but often misunderstood term. To teach it well, the term needs careful scrutiny.

The problem starts, as it usually does, with language.

‘Working’ isn’t a helpful term. Working capital suggests that this capital works, and the rest of it doesn’t.

‘Capital’ is ambiguous and slippery. If someone says capital, find out what they mean before making assumptions. ‘Capital expenditure’, ‘share capital’, ‘return on capital’ and ‘working capital’ are common accounting terms, but each has a different meaning. They are not nuanced quibbles over interpretation but big whacking differences.

Depending on context, ‘capital’ might refer to one part of equity, all of equity, all of equity and liabilities, just liabilities, just non-current liabilities, just financial liabilities, or some combination of those. In another context, people use it to describe the acquisition of non-current assets. And in another, the profit (or gain) made on the disposal of a non-current asset, as in ‘capital gain’.

Ask a banker or an economist, and a slew of additional possibilities open up. And we haven’t even started on ‘natural’, ‘social’, ‘human’, ‘manufactured’, ‘intellectual’, or ‘emotional’ capitals.

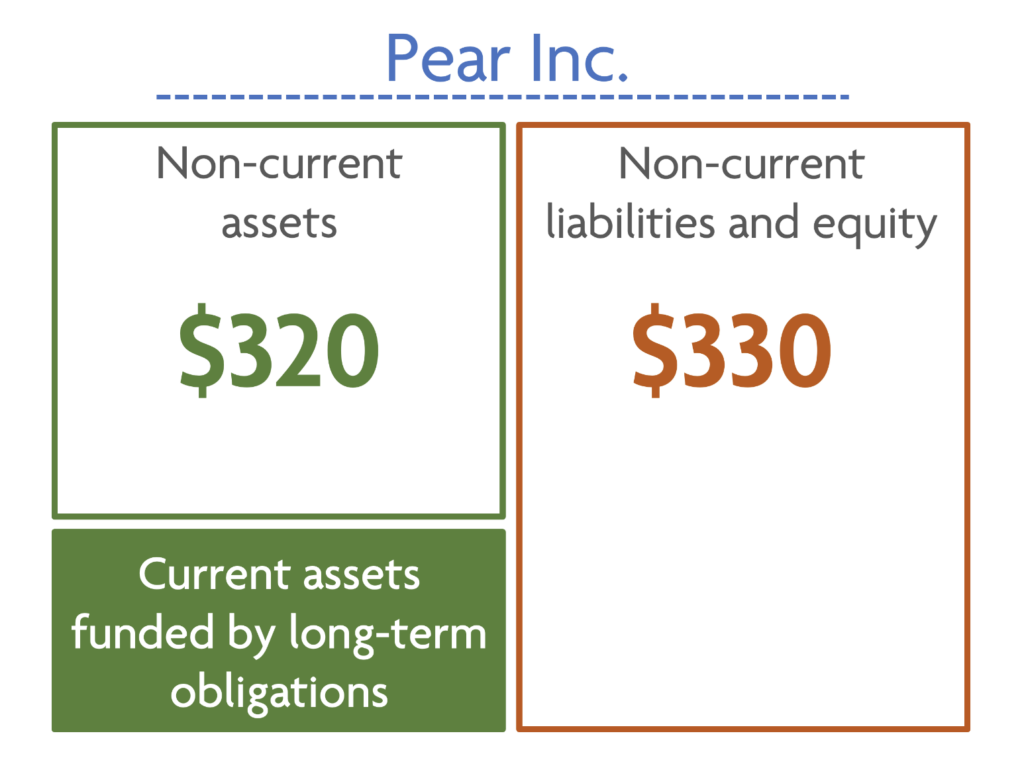

I give students an alternative calculation to indicate how much long-term borrowing is used to fund current assets.

Working capital refers to non-current obligations.

Amazingly, this is something that escapes the IFRS (See note 1 below). An explanation will clarify, but let’s first look at the traditional way of determining working capital — calculating net current assets.

Net current assets

Understanding working capital requires us to accept that current liabilities are a source of funding for current assets. This is a dubious notion that we’ll come back to, but for now, assume that it’s true.

This is different to the principles that some creditors have security over assets, or that in a winding-up some creditors take precedence over others, and that all creditors take precedence over shareholders.

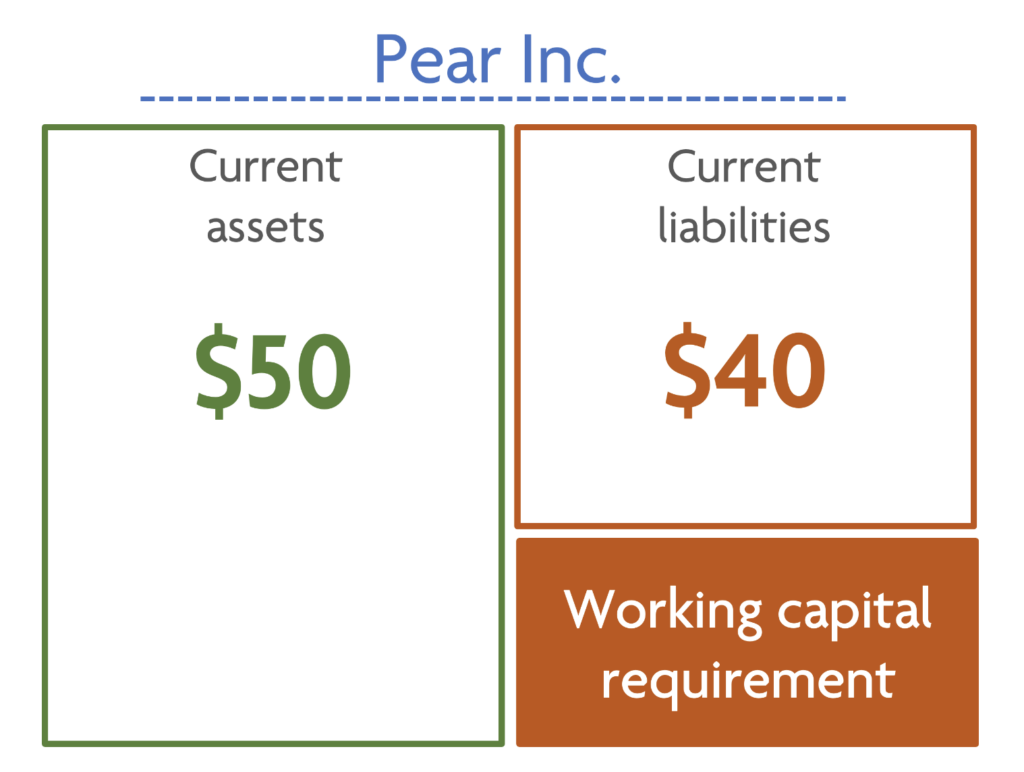

Net current assets is the difference between current assets and current liabilities when current assets exceed current liabilities. Net current liabilities is the difference between current assets and current liabilities when current liabilities exceed current assets.

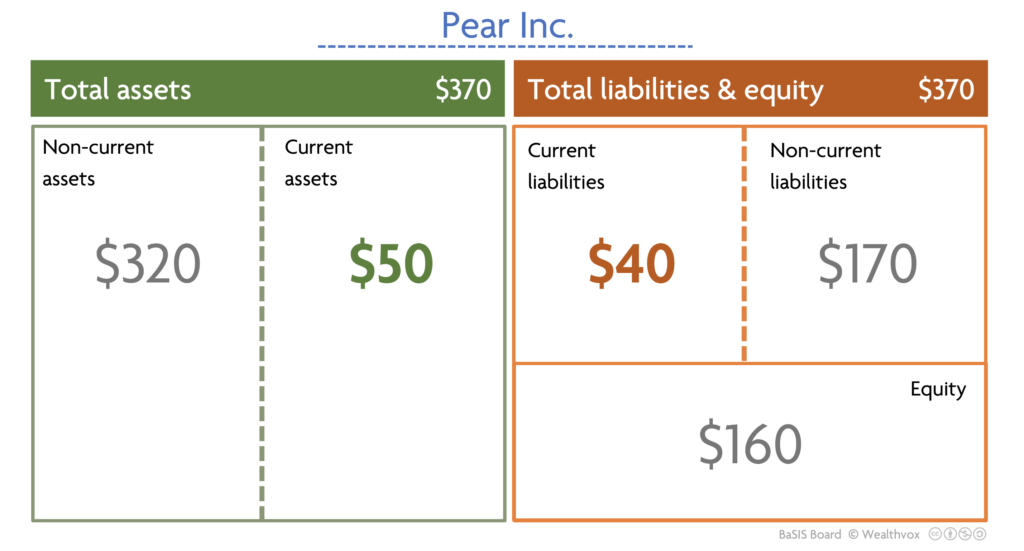

In the figure below Pear Inc. has total assets of $370 of which $50 are current. It has equity of $160 and total liabilities of $210 of which $40 are current. Current assets of $50 are greater than current liabilities of $40. It has net current assets of $10 ($50 – $40).

Assuming those notional funding allocations, we can say that current liabilities are insufficient to fund all the current assets. Pear Inc., therefore, requires additional funding — working capital — of $10. Self-evidently, this has to be non-current liabilities, equity or both.

We use current assets and current liabilities to calculate working capital, but to claim that these are the components of working capital confuses calculation with nature. Equivalent amounts are not the same as equivalent natures.

Even though they are equivalent amounts, you wouldn’t suggest that the components of total assets are liabilities and equity. I believe it’s the same error to suggest that the components of working capital are inventory, accounts receivable, cash, accounts payable, etc.

An alternative method for calculating working capital

I use a different approach with my students.

In the case of Pear Inc., we say total long-term funding sources are $330 (equity of $160 + non-current liabilities of $170). Long-term funding is first allocated to non-current assets — $320. This exceeds non-current assets by $10 ($330 – $320), and that excess is working capital.

My preferred calculation shows working capital as an obligation:

( Equity $160 + Non-current liabilities $170 )

– Non-current assets $320 = $10

However, liabilities and equity are not linked or allocated to assets. There is cash, and there is a bank loan. There is inventory, and there are accounts payable. One does not fund the other.

We classify assets and liabilities between current and non-current. Interestingly, differently for assets and liabilities. But classification does not create a link between types of assets and obligations.

Arguably, stewardship requires directors to keep an eye on their respective amounts, but the balances sit there without belonging to each other.

The current ratio

The current ratio presents similar problems because it is based on the same notional allocations of current assets and liabilities.

No ratio on its own can tell a story. Still, the current ratio may indicate the ability of an entity to meet its liabilities as they fall due, i.e, its liquidity (and ultimately, possibly its solvency too).

The reasoning is that if current assets exceed current liabilities, short-term creditors (suppliers, for example) are exposed to less risk.

Pear Inc. has a current ratio of 1.25 (Current assets $50 / Current liabilities $40).

Working capital requirements vary considerably by business type. If high levels of inventory are necessary, for example, a whisky distiller, the working capital requirement will be greater than that of a business where inventory turns more quickly, such as a food retailer.

A current ratio of 2 or more may be a sign of rude health, or it could be that the company has built up inventory that can’t be sold, and its current liabilities are falling due. Such a scenario could spell disaster for the creditors.

The quick ratio

A companion ratio, the ‘quick ratio’ or ‘acid test’ excludes inventory from current assets in the calculation, but that’s not necessarily a safe bet either.

In September 2021, Nestle, the Swiss food giant, showed that it had current liabilities greater than its current assets—it had net current liabilities. Its current ratio was 0.8, and the quick ratio 0.5. Don’t rush to short the stock—nobody’s worrying about getting paid.

Nestle has the operational strength and market power to muscle suppliers and other short-term creditors to fund its non-current assets. That’s what a current ratio of less than one means. Net current liabilities are funding non-current assets.

Conclusions

The current ratio is just one part of the story; not even tentative conclusions can be drawn without understanding the context and other available facts. There are multiple factors to consider (sector, growth, credibility, profitability), but none matters more than point of view.

- An unsecured creditor, a supplier for example, will be reassured by a high ratio.

- A bank whose purpose is to earn money from lending will, up to a point, want to provide working capital. So, lenders benefit from higher current ratios.

- There is a financial benefit to investors. Current liabilities are usually cheaper than long-term liabilities, so a current ratio of less than 1, up to a point, is welcome.

Despite what texts might say, there is no such thing as an ideal current ratio. Whatever the current ratio is, it does not tell you if the business is a safe bet, about to go bust, or whether its managers are good stewards, reckless or overly cautious.

© AccountingCafe.org

This is part of the Concepts series of articles

Notes

Note 1: In IAS 1 Presentation of Financial Statements (paragraph 70), the IFRS states:

“Some current liabilities, such as trade payables and some accruals for employee and other operating costs, are part of the working capital used in the entity’s normal operating cycle.” [My emphasis].

“Nestle has the operational strength and market power to muscle suppliers and other short term creditors into providing funding for its non-current assets. That’s what a current ratio of less than one means. Net current liabilities are available to fund non-current assets.”

I never thought of it that way. Huh. Nice.